Courage, humility, and the visual artist

![]()

This month, we will examine courage, humility, and creativity. This week, let’s take a look at how these characteristics affect the journey of a painter.

My sister-in-law, Melinda Harleman, is a visual artist in the Washington, D.C. area. She is talented, articulate, and yet unassuming—in the terms of my blog, she is humble. Courage, she says, is showing your work and bearing the storms of criticism that may (or may not) come. Plenty of visual artists display ego, but ego is not courage. Ego is fear masquerading as confidence.

Melinda Harleman, oil

Melinda Harleman, oil

Melinda Harleman started out in oils, then changed to colored pencil and worked with that medium for 25 years. She moved then to pastels, to acrylics, and finally back to oils.

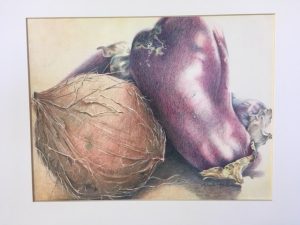

Melinda Harleman, 1st colored pencil work

In college, she began painting with oils in a desire to create luminous colors with layers of paint. Oils were the respected, kingly medium at the time. Back then, though, oils dried very slowly. With time on her hands, Melinda visited art stores and began to think about colored pencils. As a realist painter, she already liked the exacting properties of graphite.

Derwent and Prismacolor pencils had just come out. She bought some and with them she could layer orange and green, blue and yellow, etc. Her first picture was an eggplant with tiny, detailed hairs on it in shiny light brown and luminous purple, which produced a reddish purple. It was a revelation, and that work was as accepted to an exhibit. The entire staff was talking about her picture. The painting instructor told her to use just that medium. (She did notice that he watched her technique closely, and then went on to use colored pencil himself.)

My talented but modest sister-in-law admits that she was flattered. She understands that ego was in play, but it was quite understandable for a young woman back in the 1970s.

“It’s a total waste of time teaching you women! You’re going to go off and have kids and not become serious artists!” Such sentiments were literally and figuratively expressed over and over, without regret, to women as they studied with men in art classrooms. Scant attention was paid to the women, no matter how talented they were. Mel’s colored pencil work, not a medium often used then, got her recognized.

____________

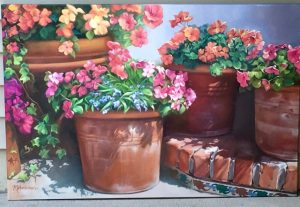

A visual person seeks visual experiences, she says. A history buff studies yesteryear, a writer searches for phrases, but an artist seeks out light, shadow, form and color. Interest for Melinda can be a reflection in the pond outside her house, of shadows, cattails, the sky. She is not a landscape artist, though. For her the world is seen in close-up focus. I find Mel to be an architect of detail: how light hits flowers, casts shadows on bricks and concrete steps—the effect of light on objects.

Melinda Harleman, acrylic

The blank canvass is scary. Fill me! it screams. With what? we whimper back. Here is how this realist paints. In this example, Melinda uses oils:

“Take old memories and give them a fresh look. What will you paint today? Look through the photos you’ve taken and see what tickles your fancy. On your computer, crop a photo to take out the unnecessary things. The final cropped portion becomes a rectangle, a square, etc. Thus, you get a canvas to fit your vision.

Paint the whole canvas light gray for a medium ground so you can base lights and darks well.

Take a vine charcoal (very soft) and make the ‘cartoon’ of the painting—blocked out color fields in outline.”

Do the hardest parts first—the details in color. If those hardest parts cooperate, continue with the canvas from there. Move color all over the canvas in a push and pull of what works. It is an exacting process.

With oils you work from dark to light. You look at the photo, then you start putting light into the painting. You’re creating not only a flower but the light that hits the flower. You’re pulling it out and fooling with it, you may hate the result, but then you fool with it again. You go to the next flower, but you reinvent that flower in a different way: putting on paint, mixing it in, bringing out light from the darkness, and infusing it with color and life.

Melinda Harleman, oil

That is euphoria, time does not exist. You are in the groove, but you never start out in euphoria. Sticking with the work until it feels right is the only thing that brings on euphoria. It’s tough, but you can use this in every aspect of your life. If you don’t learn how to get over the fear of starting, you don’t get to euphoria.”

____________

(Greta here: Oh, how we need to learn to push through the pain of starting things! Just imagine the productivity we would all enjoy if we made ourselves start. It takes courage but also humility to start, to face the white canvas or page that cries out for a creative’s attention: courage to face the blankness, and humility to accept that our day’s efforts will not produce perfection.)

____________

The question Melinda is asked most often is, where do you get your ideas?

My husband and I experienced the following example walking through New York City with Melinda in the autumn of 2008. At that time of the Great Recession/the Crash, her day job was as a loan processor, a Document Specialist, in banking.

Below, she explains how the inspiration for the artwork occurred. Her painting is in two panels: one is 30”x40”, the other is 30”x24”.

“ So much of what I saw that particular day was the result of horrific events.

The gates surrounding St. Paul’s Chapel, where the 9/11 firefighters sought refuge during their efforts, were still weighted down with displays of sympathy and sorrow. The church’s sanctuary had been turned into a memorial. We stood looking at a gaping hole, like a decayed tooth, that used to be the World Trade Center. To the side, a huge skyscraper was being knocked down, deconstructed. The process was ugly.

We walked past Washington Mutual and saw a ‘Closed’ sign in its window. I stopped in my tracks, and what was happening with the economy hit home. It was the deconstruction of everything we knew.

Wall Street was too quiet, too taut, and my banker’s mind felt as if people might suddenly jump out of the windows.

But at Union Station and the Chrysler Building, the reflections of surrounding buildings in other buildings fascinated me. Their beauty brought everything back into my world, through form and design and abstraction, but with outlines based in reality. I took hurried photographs, and when at home, I began to paint.

I worked pane by pane, rather than my usual way of moving paint throughout a canvas. As I painted window by window, I saw the rich tapestry of color and abstractions, and yet the detail that went into each pane.

Melinda Harleman, NYC painting in process, oil

The bank at which I worked was not disciplined by the government. The owners had decided early not to enter into the subprime loans that had caused the Crash. Their philosophy was that each of us was valued as we labored to create a whole. This mindset fed me. I worked in silence, creating a painting whose subject was the capital of United States banking.

As I painted, I thought of New York City as a tapestry of neighborhoods that make a rich, multicultural whole. Each pane I painted was a neighborhood. It wasn’t just one whole, it was a painting within a painting. In my mind, NYC was similar to a multiple-paned window with it’s interlocking neighborhoods, cultures, businesses and entertainment areas. The distortions in each pane were especially interesting, reminding me of the pulsating rhythms of that city. I worked over a year, much longer than usual. My mind journeyed to a place where things are purely artistic. Outside my room, the Crash raged. But by doing this painting, I relaxed. I could make sense of the world, my world.”

Melinda Harleman, the finished NYC painting, acrylic

Thank you, Melinda Harleman, for years of being able to discuss the creative arts with you and benefit from a God-given talent that you have married with hard work, producing gorgeous paintings!

____________

Greta’s postscript: The eye of the beholder will always bring something personal to a painting, whether or not that eye is educated in art. Melinda sees hope, and I thank her for that. My sober, more grinch-like Mennonite eye sees a warning, as well. The wavy reflections in her beautiful painting are echoed in what I saw last year (2017) at the new 9/11 Memorial Plaza. The church and surrounding buildings are now reflected in a new, glass high-rise on the site. To me, the waviness of their reflection makes it look as if those buildings are fragile and able to crumble—at the drop of a loan and a nasty snicker of greed.

____________

I welcome your comments: gretaholtwriter.com/blog.

{Thank you to my niece, Addie Liechty, for taking the picture above that is this blog’s featured image. Her blog is: https://addieswriting.wordpress.com.}

Best wishes and have a good week.

Greta

Thanks to your sister-in-law for articulating her process and product. It is very detailed work. And thanks to you, Greta, for sharing this. I want to share it with an artist friend.

Oh, please do! Melinda’s talent, and her quiet acceptance of it, have place me in wonder since I met her as a high schooler, years ago.

[…] Here’s an interesting blog read on a set of topics that are more related than most of us think: courage, humility, and the visual artist. If you stop by, tell Greta I sent you. […]

Thank you, Frank. Your long-standing and popular blog, afrankangle.wordpress.com, is an excellent source of interesting posts!

Such an interesting post, Greta! Loved learning about Melinda’s process–and seeing her work–stunning! Just as you saw the fragility in the wavy reflections, I was struck by Melinda’s capturing “pane by pane.” I live in NY and was personally and deeply affected (like so many others) by the crash. Reading Melinda’s description, I couldn’t help thinking of the homophone: pain by pain. So many individual panes of glass … so many individual pains.

Such a beautiful response, Diane. Beautiful! Please let me know how your writing projects are progressing.