Kilt and Cap: being half-Mennonite

![]()

Recently, a friend and fellow blogger, Diane Gottlieb, asked me about my Anabaptist background. Diane writes the wonderful blog WomanPause, regarding women in the glorious years. Her questions made me think of a memory I wrote in response to J Daniel Hess’s presentation at one of the previous Mennonite Arts Weekends. The Weekend is coming up again in a few weeks! (February 7-9 in Cincinnati) The memory is one of so many that remind me I do not measure up to the Anabaptist vision.

___________________________________

Kilt and Cap

My dress ballooned around my legs as I climbed onto the speech teacher’s desk and labored up three stacked chairs to the top of the temporary wall. Teetering on the highest chair, I peered over. Ten feet below, my keys sat on the table where I’d left them before pushing the lock button on the door and closing the door behind me. My car and house keys, and the keys to this very room twinkled, just out of reach.

I thought I might make it.

The prayer cap, filmy white and crisp with propriety whispered a warning into my right ear. ‘Plump, middle-aged teachers don’t jump into locked rooms to get their keys.’

“Not even so they can keep working until the sun sinks?” I replied. “I’m trying to be good, you know.” The cap disappeared, its ribbons flicking back like a tsk.

I was used to this kind of interference. The marriage of my parents—a sober Swiss Mennonite and an irreverent Scot—had brought forth two imps. Each inhabited a shoulder: one imp was represented by a white prayer cap and the other by a rough sewn kilt. One minute I would listen to the peacemaker, the next to a screeching warrior skinning a glen of its heather in a rush to battle. It could be quite tiring.

The time was 5:30 p.m. and I had to get home to grade papers, make calls to the parents of shaky students, cook dinner, plan the next day’s events, and maybe get to watch a show by 10:00 p.m. Thank goodness for “Law and Order” reruns. The bad people rarely won; it was relaxing for this Mennonite to watch.

In the distance, I heard workmen slice up yet another section of the school. The air conditioning had pooped out when the first jagged-toothed saw neared an electrical line. For three weeks, my kids with learning disabilities and I had sweltered in our fifteen-by-eight foot cell. The cell was sandwiched in the middle of two other tiny rooms: one for the psychologist, the other for the speech teacher. Up here on the wall I could hear the imagined giggles of students and smell the accumulation of old sweat, theirs and mine.

‘Eiye, dearie,’ brogued the kilt into my left ear. The kilt gave me a sharp nudge. ‘Whatcha waitin’ for, love?’ I wasn’t scared of my kilt. I’d taken it’s dares since childhood: swinging high and fast on the monkey bars above the playground until even the boys begged me to stop; skipping on the lip of a bridge over the town’s swollen creek. Much later on trips with my husband, I might run to the edge of Southwestern bluffs peering over the sides into jagged wastelands; and I’d insist on the cliff walking appointment or the two seater flying lesson. My husband, a master of courage with all the problems people could cause, would blanch and roll his eyes. I loved him, but I wasn’t going to stop. I could take only so much of the cap with its precision, its prudence.

The bagpipes whined, and the kilt twitched its hem and grinned. Distant forests of blue-faced fighters and hidden man-eating clans painted themselves across my canvass. I grasped the skeletal struts of the torn ceiling. ‘Let us pray,’ murmured the prayer covering as a tri-metered tune by Alice Walker poured forth from an a cappella choir. ‘Bugger it,’ said the kilt, and I jumped.

Halfway down I knew I was cooked: nay, sliced, diced, filleted, and fried. The second I’d jumped, the struts squealed and broke from my weight. Steel ripped from aluminum. By swinging my legs out in front of me to prevent cracking my feet on the wall, I’d created a perfect diving position for a back flip: the position at the start of the flip in which the contestant is sitting in the air as if in an easy chair with her legs straight out front. I dropped ten feet and hit bottom. Then, as if swinging from a rusty, broken hinge, my top haIf fell back, and I flopped on the floor like a fish in dry air.

Gradually, I could hear the spin of saws and the indifferent calls of workmen. Air rushed into my lungs. I’m hurt, I said. No one answered. I rolled onto my side, gasped at the sharp pull in my back, and crawled over to the desk where my keys winked innocently. Purse and briefcase found their way into one hand. Without knowing if my skeleton still joined the muscles of my body, I used a large book, a rickety chair, a round table and the makeshift wall to rise. Dizzy but determined, I turned the door’s inside knob and watched ruefully as the lock popped open. The lock’s ‘yes was yes’, and its ‘no was no’, an important lesson we Mennos learned in eighth grade catechism class, when they told us we couldn’t take oaths on the Bible.

I hobbled down the hall, wondering how I would traverse the four flights of stairs. Pain and shock accompanied me, and the three of us clung to the banister, hoping the railings’ joists could handle the burden. I congratulated myself on my routine of staying long after the kids had gone—when the highway traffic patterns were better. No one saw me. Achieving ground level, I ignored the kids in after-school care who tugged at my clothes while yelling that so and so had stolen their snacks, and staggered out to my car. I don’t know how I got home; to this day those lost moments frighten me. Who knows what state one’s fellow drivers may be in: reeling from the last boilermaker before facing the wife and kids; furious at unsolvable problems at work; giddy from a stolen kiss; or loopy from a ten foot drop.

At home, I showered blistering water onto my back: bent over, grasping at the tiles, trying not to pass out. I was hurt.

_________________

Two months later, I am at a hallowed northeastern writers’ conference, where surprisingly one of my stories has been accepted. I’ve become acquainted with physical therapy, and I ingest kilos of aspirin per day, no hard stuff—after all, my mind is already distracted by magical beings that talk at me.

A venerable institution, the writers’ conference is in the early stages of jettisoning its outmoded system of hand kissing the Great Ones—butt kissing, insists the kilt—to a more egalitarian and multicultural environment. The conference does retain its hierarchal framework: its cadre of young dining room waiters say openly that they hate serving us but love the status of having been selected; and its designated Scholars (stories published in high class journals) and Fellows (book published by acceptable presses) add luster to the proceedings. Our workshop is led by a wise man of writing, a modern Great One who doesn’t want slurpy homage. He runs a tight ship, and we learn from each other. I’m a little intimidated, although grateful to be here.

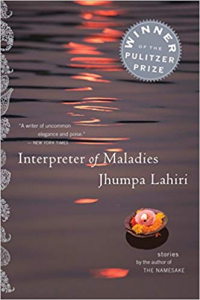

One evening, a young woman stands behind the lectern of the Great Hall where celebrated writers have stood, and reads the title story of her collection. She is beautiful; her quiet, confident voice floats along the cultural hills and valleys of an Indian story (‘Asian,’ corrects my politically correct prayer cap). Every phrase is poetry, the subject wistful and sad. The writer and her craft are kissed by the gods. Afterward, I run-walk to my car and drive hairpin curves down the mountain— past the forests of a beloved American poet— muttering about deluded would-be writers like me, losers who think they’ve come close to having something to say and the words to say it. I am such a fool. ‘Patience,’ whispers the cap; the kilt screams a ‘sluagh-ghairm’. How could I know the girl behind the podium is about to win a Pulitzer Prize?

I get to read at the podium late one night, when we contributers may read to each other, if to no one else. I must admit that, even though they are a bother, both the cap and the kilt do join forces to help me perform. My father used to say that his grandmother, an old school Scot with an almost indecipherable accent, would give her unfailing advice to ‘keep your pecker up’ whenever things got tough—I think she meant ‘nose’. I did have the nerve to perform; thus, the kilt. But my Mennonite mother instilled in us a desire also to share our talents, not only compete against others; thus, the prayer cap. One can’t be a shrinking violet in the halls of a writers’ conference, but it does help to give of yourself, rather than chase the competition, in the four minutes offered. Yes, four minutes to read a few lines of your work; go one second over, and they’ve threatened to turn the lights off on you. Imagine the embarrassment. Reading at the lectern where your betters have read, running one second over your allotted, tiny four minutes, and having the lights go out, leaving the hall in darkness. Nobody chances it. I read as fast as I can, and it’s fun.

Another day, I attend a lecture by a famous Bengali woman writer. She speaks of writing across cultures: the struggles and rewards, the misunderstandings and angry protests when writers are cheeky enough to write in the voices of people outside their ethnicities.

I am so impressed by her trials that I begin to wonder about the cap and kilt that are my constant companions. Although my parents were crazy in love, their marriage could be a sports field at times, where two cultures clashed. Even though both people were white, I insist upon giving myself permission to claim bi-culturality. And I’ll fight—I mean, debate— anybody who says I can’t. Hoping I sound even a bit urbane, I write about this to the Bengali lecturer, and she agrees to see me. We have a good talk on the porch of one of the faculty houses. We talk of courage and of culture. I follow my softer instincts; the prayer cap nods approval. By speaking quietly and listening well, I achieve the right tone of interest and respect. It is a perfect moment. But when a fly buzzes around my head, alighting on my teacup numerous times, and landing on my arm, I whack it a good one, stunning the fly in front of the Hindu who has been kind enough to give me a moment. The kilt skitters behind a rock, laughing.

Near the end of the week, when my piece is critiqued by my workshop, the comments are pithy and pointed. In the story, an American careens along a pocked road in the outback of Botswana with a white Afrikaner of dubious intent. My fellow writers spend time on it, arguing about the characters, which, I hope, is a sign that the writer might have hooked ‘em. That, or they simply don’t like it and are energetically trying to fix the story’s flaws. In any case, after the nervous nellies subside, I’m feeling relieved.

It is time for the personal interview with the Great One, the leader of our workshop. Displaying wisdom, he intuits that I really care more about the Afrikaner than the American, because I’m interested in the nature of evil. He is not surprised to learn that I am a Mennonite. I drop a few Swiss phrases, just because I can’t help myself. It seems wise to have a personal shtick here. We talk a long time, and we walk into the Great Hall a few minutes late. Another Indian or Bengali or Pakistani is reading a wondrous story. “And no-o-o one can please you, not even God,” she intones.

Where will we sit? The rows are blocked by railings and we are walking in on the reader’s one chance to impress the Great Ones sitting in the audience. She gets to read during the daytime. She is a waitress, one of the chosen, closer to coronation than the rest of us.

People are looking at us; we must sit down. My prayer cap whispers, ‘Let him lead, be calm, you’ll work this out.’ But, determined to get out of the way, and in need of action, I hear bagpipes. Beginning with the faraway wails of one whiny pipe, the sound swells to the blow-back force of an army. The kilt dances in impatience and cries, ‘Come on, ye lads!’ Raining down upon us are men in kilts and women in homespun, wielding axes and screaming battle cries, as they pound the meadows toward sure destruction.

‘Dinna’ dae d’ wrong thing,’ starts the prayer cap in confusion. ‘Wait…’

‘Ayyyeeee!’ screams the kilt.

I stride to the middle of the hall, where the rows are divided. All of me swings up under the steel rails of the fifth row. I push myself under the bars and that’s when it happens. The Injury-of-the-Classroom-Keys kicks in and I can’t move. People stare in horror as an ample woman swings on the struts like an old acrobat unable to go up or down. ‘And no one can please you, not even God.’ My Great One gives me a push very close to my rear end; I struggle and thrash under the railings, and crab crawl to the nearest seat. The Great One throws himself up over the bars and gracefully lands in his seat in male sprawl. I am conscious of his long body beside mine. I chance a quick look about, realizing that had I followed my prayer cap’s advice, I could have taken six more seconds and found the other side of the auditorium, whose stairway was open and clear. We could have walked, like decent people, to our seats.

Unable to escape the disgusted expelling of the assemblage’s breath, I hang my head. The horror. Why do I have to be me?

The cap says, ‘It’s all right, cherished child of God. It will pass. Just think of all the people in the world who have had to live through much worse. Those in poverty, in war, imprisoned by the whims of tyrants; those for whom justice is only a dream.’

I unclench my hands, then my jaw and try to sit straight, ignoring the open mouthed disapproval of the people nearby who have been assaulted by my show of force. I am an alien, and unfortunately, I do have a shtick; I will be remembered. Beside me, my workshop leader pretends that nothing has happened, probably a reason he is a Great One. I listen to the talented girl at the lectern. I do have to admit to being a bit tired of the collective talent of the Asians. But attention is returning to the front of the hall; no one has died. The speaker spins her tale, and I begin to feel as if this whole incident, although nightmarish, has been merely a dissonant note of Pan’s flute, half sounded now gone. Sunlight peeks through the branches of his mythical forest. I warm to my vision and begin to feel a comfortable lightness of being. The prayer cap floats down and settles on my shoulder like Jesus’ breath. I’ll regain my poise and my inclination to share.

Nipping my ear, the kilt breathes, ‘Eiey, but ye’ve nothing on under your apron, dearie.’

I slouch in my seat, scheming to murder—I mean, to develop a balanced life that will no longer include my two companions.

_______________________________________

Link for first cap: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/458593174539850941/.

Link for kilt: https://www.atlantakilts.com/store/ladies-kilt.html?gclid=Cj0KCQiA04XxBRD5ARIsAGFygj-lQVrGMmTyZlzbFHBZkZhShM5QIz9li6cR-JAg2kSBmUhAFET8GrEaAvO_EALw_wcB.

Link for Jhumpa Lahiri: https://www.amazon.com/Interpreter-Maladies-Jhumpa-Lahiri/dp/039592720X/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=interpreter+of+maladies+jhumpa+lahiri&qid=1579279474&sr=8-1.

Link for stunned fly: Photo by Viggo Jorgen on Unsplash.

Link for warrior: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oMgQ7x2T9Yg.

Link for second cap: https://marianbeaman.com.

______________________________________

I welcome your comments: gretaholtwriter.com/blog.

{Thank you to my niece, Addie (Liechty) Kogan, for taking the picture that is this blog’s featured image. Her blog is: https://addieswriting.wordpress.com.}

Best wishes and have a good week.

Greta

Greta! What a wonderful piece–so tender, so reflective, and sooooo very funny! I found it absolutely delicious and love how your parents, along with their caps and their kilts, play in your life.

Thank you for this!!

I often wonder what people who are ‘homogenous’ feel!

Delightful! So descriptive and entertaining! Loved it!

Thanks, MJ! I miss Bluffton.